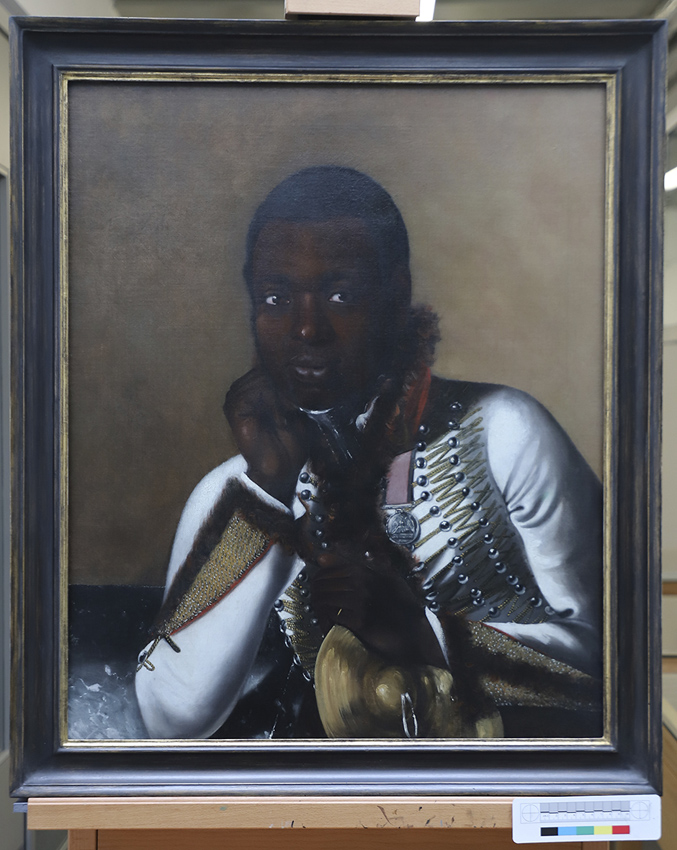

The portrait of Waterloo bandsman identified as Pte Thomas James by the National Army Museum, shown after restoration as it is now on display.

Catalogued as ‘early 19th century English School’, the picture came to Gorringe’s of Lewes, East Sussex, in December last year from a local private collection. It had apparently been inherited by the vendor from their father, although nothing further was known of its history.

As featured on the cover of ATG No 2673, the 2ft 5in x 2ft (74 x 62cm) oil on canvas drew strong competition and sold for a hammer price of £30,000 (estimate £3000-5000) to an institution – now known to be the National Army Museum in London, with support from Art Fund and private donors.

The front page of ATG No 2673 in December 2024, reporting the sale at Gorringe's of the portrait of a Waterloo bandsman now identified as Pte Thomas James by the National Army Museum.

The museum’s research has revealed the bandsman to be almost certainly Pte Thomas James, a percussionist in the 18th Light Dragoons and one of only nine black soldiers known to have received the Waterloo Medal, the first British medal awarded to soldiers regardless of their rank (made of silver with a crimson ribbon edged in dark blue, some 39,000 medals were issued).

The portrait has been dated to 1821 and attributed to Thomas Phillips (1770-1845), whose more typical sitters were Georgian luminaries such as the Duke of Wellington and Lord Byron.

According to Artprice.com, the auction record for Phillips stands at £51,500 (£62,000 with buyer’s premium) for an oil on canvas, Portrait of Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820), sold at Sotheby’s London in 1993. If the attribution is correct, the price at Gorringe’s would be within the top five prices for Phillips.

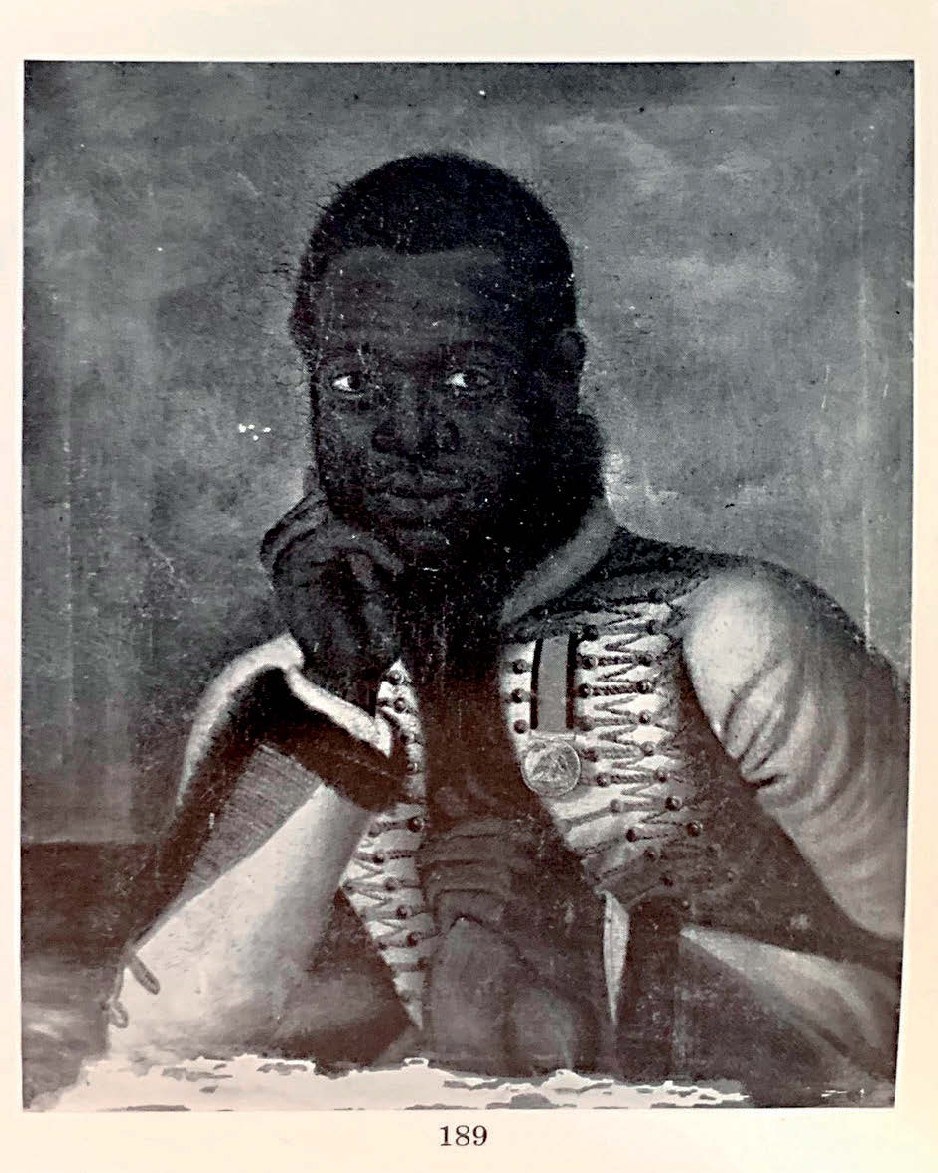

Interestingly, a similar version of this portrait sold at Christie’s for £210 in 1972 where it was catalogued as ‘American School, c.1820’ and the sitter, who is also shown wearing the Waterloo Medal, was described as ‘probably from the 33rd Foot’.

The similar version of the portrait of a black bandsman that sold for £210 at Christie’s back in 1972, as displayed in the catalogue at the time.

Distinctive dress

The cymbal and fur pelisse suggested that the sitter was a percussionist in a cavalry regiment. These details helped to narrow down the possibilities until a likely candidate emerged.

During the late 18th and early 19th century, a number of black men are known to have served in various regiments either as trumpeters or bandsmen; the latter playing percussion instruments such as cymbals, tambourines, big-drums and kettle drums.

Military musicians played a vital role both on and off the battlefield. Drums, fifes, and trumpets were used to relay commands during combat, while bands provided entertainment, boosted morale, and helped recruit new soldiers.

While their service was often restricted to musical roles and they were denied promotion, in a few instances black soldiers became trained soldiers and participated in direct action.

Some had been recruited into the army via units stationed in the Americas, the Caribbean and India, while others from the resident black population in Britain and Ireland enlisted locally.

Born in 1789, Thomas James came from Montserrat in the Caribbean and served with the 18th Light Dragoons after coming to England in 1809. At Waterloo he did not take part in the battle but was severely wounded while defending officers’ baggage from looters. Alongside others in the detachment, he was awarded the Waterloo Medal.

It is believed that a senior officer may have commissioned the portrait of James in gratitude for his efforts (as a private he would not have been able to afford a commission). It is likely to have been displayed in an officer’s mess or similar army establishment, but over time, Thomas’ identity was lost. Although the identification is not completely certain, the museum’s research shows that James is very likely to be the mystery musician.

James continued to serve for a few years before leaving the service and receiving his military pension

In-depth analysis

The portrait sold by Gorringe’s was far from perfect in terms of its condition – it had been relined 20-30 years ago but had plenty of dirt, bituminous bubbling and a shiny varnish to the surface.

After acquiring the painting, the museum worked with Lincoln Conservation (University of Lincoln) to conduct an in-depth analysis of the artwork using specialist techniques. Lincoln was asked to conserve the painting, making it ready for display and to undertake cross-sectional sampling, polarised light microscopy, infrared photography, and X-ray fluorescence (XRF).

The museum says: “This work enabled a deeper understanding of the materials used by the artist and confirmed the date of its creation and helped uncover original details and renewed the painting to its former glory.”

The artwork will be on permanent display in the Chelsea museum’s Army at Home gallery.